Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP)

November 7, 2025

What are the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP)?

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) are the standardized rules and guidelines that govern how companies prepare and present their financial statements. In the wake of the Great Depression of 1930s, when investors had lost faith in corporate numbers, U.S. regulators and the newly created SEC began driving the adoption of uniform accounting standards. Over time, these efforts crystallized into GAAP, a safeguard designed to restore confidence in financial markets. Nearly a century later, GAAP continues to serve as the bedrock of U.S. financial reporting, ensuring transparency and credibility across more than $50 trillion of U.S. equities.

Key Learning Points

- GAAP emerged after the Great Depression to restore investor trust and remains the backbone of U.S. financial reporting

- It governs how companies prepare their financial statements and is codified by the FASB into Accounting Standards Codification (ASC)

- Public companies must comply with GAAP, while private firms benefit from following it when seeking financing or credibility

- GAAP vs. IFRS differences (leases, inventory, impairments, revenue recognition) have significant valuation, credit, and M&A implications

- Non-GAAP measures (adjusted EBITDA, core earnings, free cash flow) are widely used by analysts for valuation but must always be reconciled back to GAAP to avoid bias or misrepresentation

Why was GAAP Introduced?

Before GAAP, companies in the U.S. had significant freedom in how they reported financial results. This lack of standardization created inconsistencies, confusion, and opportunities for outright fraud. While the 1929 crash was driven by speculation, leverage, and weak banking oversight, the absence of standardized reporting deepened the loss of investor confidence and highlighted the urgent need for stronger accounting rules.

In response, the U.S. government passed the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. These landmark pieces of legislation created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and gave it the authority to establish accounting standards to protect the investing public. The SEC, in turn, worked with the private sector to develop a standardized framework. The term “Generally Accepted Accounting Principles” was first used in 1936 by the American Institute of Accountants. Over time, the responsibility for setting and maintaining GAAP evolved, eventually being taken over by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in 1973.

Although the term GAAP was first introduced in 1936, the framework was still in its formative stages. Over time, a series of events shaped it into the comprehensive system we know today. For example, a prominent financial fraud that highlighted the need for standardized accounting before GAAP was the McKesson & Robbins scandal of 1938. The company’s management fabricated millions of dollars in assets, including inventory and accounts receivable, to inflate its reported profits. This fraud was only possible because, at the time, there were no clear rules requiring auditors to physically verify inventory or independently confirm receivables. The scandal directly led to new auditing standards and reinforced the need for the structured framework that would become GAAP. There were many such events that occurred from time to time, each leading to suitable changes in GAAP and ultimately making it more credible and robust.

How does GAAP Work, and Who Sets it?

GAAP works by setting out a standardized framework for how companies record, classify, and present financial transactions. At a practical level, it governs the preparation of the three core financial statements, income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement, along with supporting disclosures that ensure transparency.

The rules are set by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) into Accounting Standards Codification (ASC). Companies must apply these standards consistently so that their results can be compared across time and against peers.

GAAP Example: ASC 606 Revenue Recognition

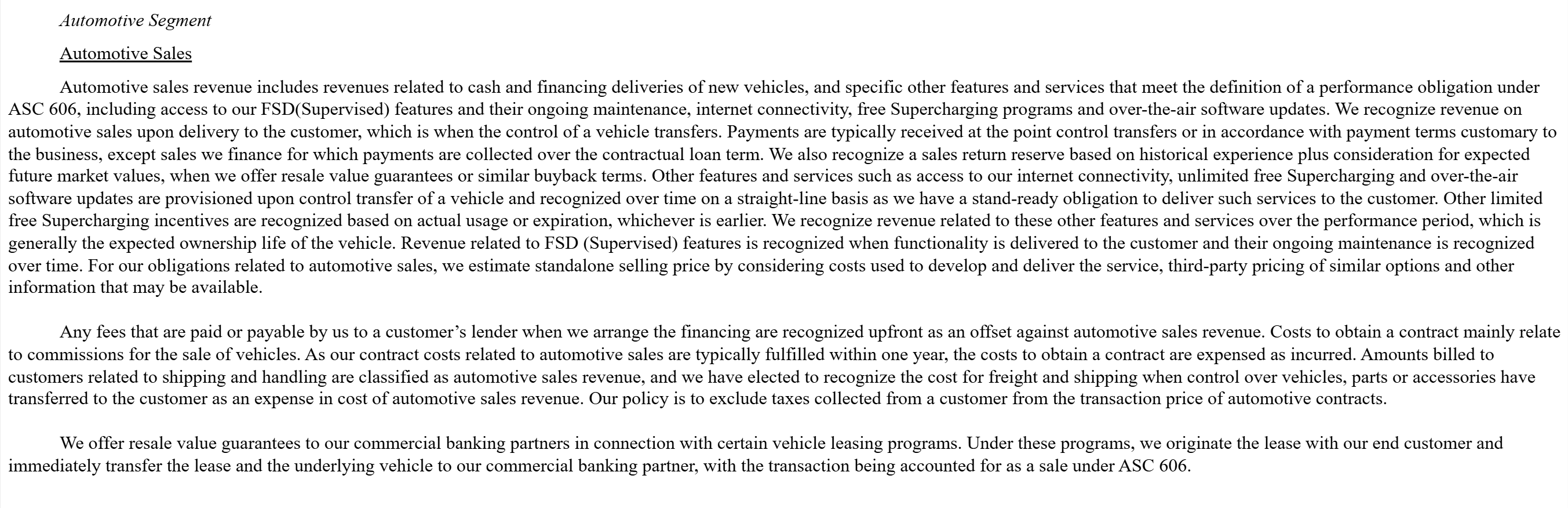

For example, Tesla’s FY 2024 10K report clearly explains how it recognizes revenue in line with ASC 606.

The following snippet highlights how Tesla disaggregates its revenue by major sources.

Source: Felix

Source: Felix

The following snippet highlights how revenue is recognized on automotive sales, specifically upon delivery to the customer, when control of the vehicle transfers.

Source: Felix

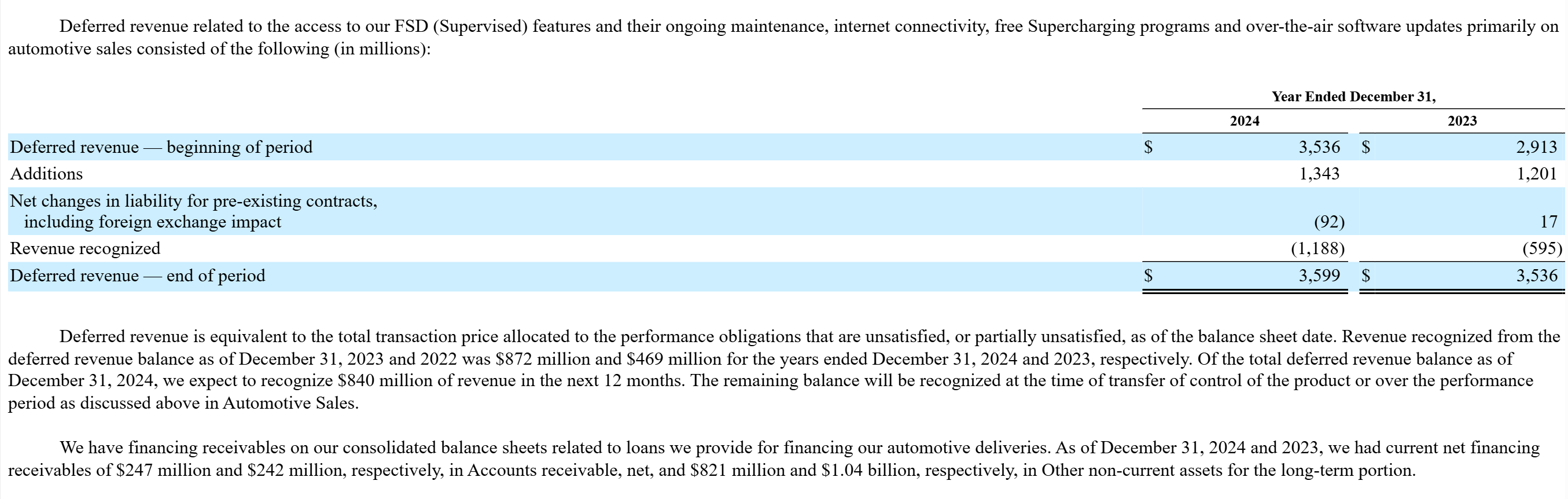

The following snippet highlights deferred revenue, and how much of that deferred revenue is expected to be recognized over the next 12 months versus beyond.

Source: Felix

Why is GAAP Important and What are its Core Qualities?

GAAP is not just a checklist of accounting rules, it is the framework that underpins trust in financial reporting and, by extension, in capital markets. Its importance lies in reducing information asymmetry between company insiders and external stakeholders, ensuring that investors, analysts, and regulators can make informed decisions based on reliable data.

At the heart of GAAP are four qualitative characteristics that make financial information decision-useful:

Relevance

Financial data must provide insights that influence economic decisions, helping investors evaluate past performance, current position, and future prospects.

Reliability

Reported numbers must be accurate, verifiable, and free from bias, ensuring stakeholders can depend on them when allocating capital.

Comparability

By enforcing standardized reporting, GAAP enables meaningful analysis across companies, industries, and time periods.

Consistency

Firms must apply accounting methods in a uniform way over time, so performance trends reflect true business fundamentals rather than shifting reporting practices.

The above qualities explain why GAAP is indispensable. For capital markets, this standardization is what keeps valuations credible, credit ratings consistent, and deal-making transparent. Without GAAP, financial statements would become fragmented, eroding trust and efficiency in the system.

What are the Core Principles under GAAP?

GAAP operates on ten fundamental principles that guide financial reporting:

Regularity Principle

Organizations must strictly follow all established GAAP standards without deviation.

Consistency Principle

Accounting methods must remain uniform across all reporting periods to enable meaningful comparisons.

Permanence of Methods Principle

Financial reporting procedures should be maintained consistently throughout all financial document preparation.

Sincerity Principle

Accountants must demonstrate complete commitment to providing accurate and objective financial information.

Prudence Principle

Financial entries must be based on factual evidence rather than speculation, ensuring realistic and timely reporting.

Utmost Good Faith Principle

Every participant in the accounting process must act with complete honesty and truthfulness.

Non-Compensation Principle

Companies must present all aspects of performance and position, whether favorable or unfavorable, without offsetting assets against liabilities or revenues against expenses. Each element must be reported separately to ensure transparency and comparability.

Materiality Principle

Financial reports must contain all factual information necessary to fully reveal the entity’s financial position, with assets recorded at cost.

Continuity Principle

Asset valuations operate under the assumption that the business will continue operating indefinitely.

Periodicity Principle

Financial reporting occurs within standardized, consistent time intervals such as fiscal quarters or annual periods.

Where is GAAP Used?

Public companies in the United States are legally required to comply with GAAP when preparing their financial statements to maintain their listings on stock exchanges. GAAP is also widely adopted by government entities, where standards are set by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) rather than the FASB. All 50 states follow these principles, along with many local bodies such as counties, municipalities, and school districts.

While privately held firms are not obligated to follow GAAP, it is often considered prudent. Adhering to GAAP enhances credibility, facilitates debt financing since lenders prefer GAAP-compliant financials, and can even reduce the likelihood of heightened tax scrutiny from regulators.

GAAP vs. IFRS

While GAAP is primarily used in the United States, most other countries follow International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), which serves a similar standardization purpose internationally. GAAP is rules-based, providing specific and detailed instructions, while IFRS is principles-based, offering a broader framework that requires more judgment. This distinction leads to material differences in financial reporting.

From the point of view of financial analysts, understanding the difference between GAAP and IFRS is critical, because the framework a company uses can materially impact the numbers that flow into valuation models, credit assessments, and deal negotiations. Following are the key differences between GAAP and IFRS:

Inventory

GAAP permits companies to use FIFO, LIFO, or Weighted Average for inventory valuation, offering flexibility but reducing comparability across firms. IFRS, by contrast, prohibits LIFO, requiring either FIFO or Weighted Average.

In inflationary environments, LIFO typically results in higher COGS and lower reported profit (since the most recent, higher-cost items are expensed first). In deflationary environments, the reverse holds true, LIFO leads to lower COGS and higher profit.

For analysts, this difference significantly impacts the comparability of gross margins and inventory values between companies.

Leases

Both frameworks now require the capitalization of most leases on the balance sheet. However, IFRS (IFRS 16) classifies nearly all leases as finance leases, whereas GAAP (ASC 842) maintains a distinction between operating and finance leases. The GAAP distinction can have a different impact on the financial statements, as the P&L expense recognition is a straight-line expense for operating leases but front-loaded for finance leases.

Leases with 12 Months or Less of Term

- Both GAAP and IFRS has same treatment, where companies can choose to avoid balance sheet recognition

- Lease payments are recorded as expenses in income statement

- For example: For 8-month equipment rental at $1,000/month, $8,000 expense will be recorded in the income statement in case of both GAAP and IFRS

Leases with More Than 12 Months of Term – with Operating Lease

IFRS: Eliminates the distinction between operating and finance leases for lessees. Under IFRS, all leases longer than 12 months are treated like finance leases. The accounting treatment is explained in the next section.

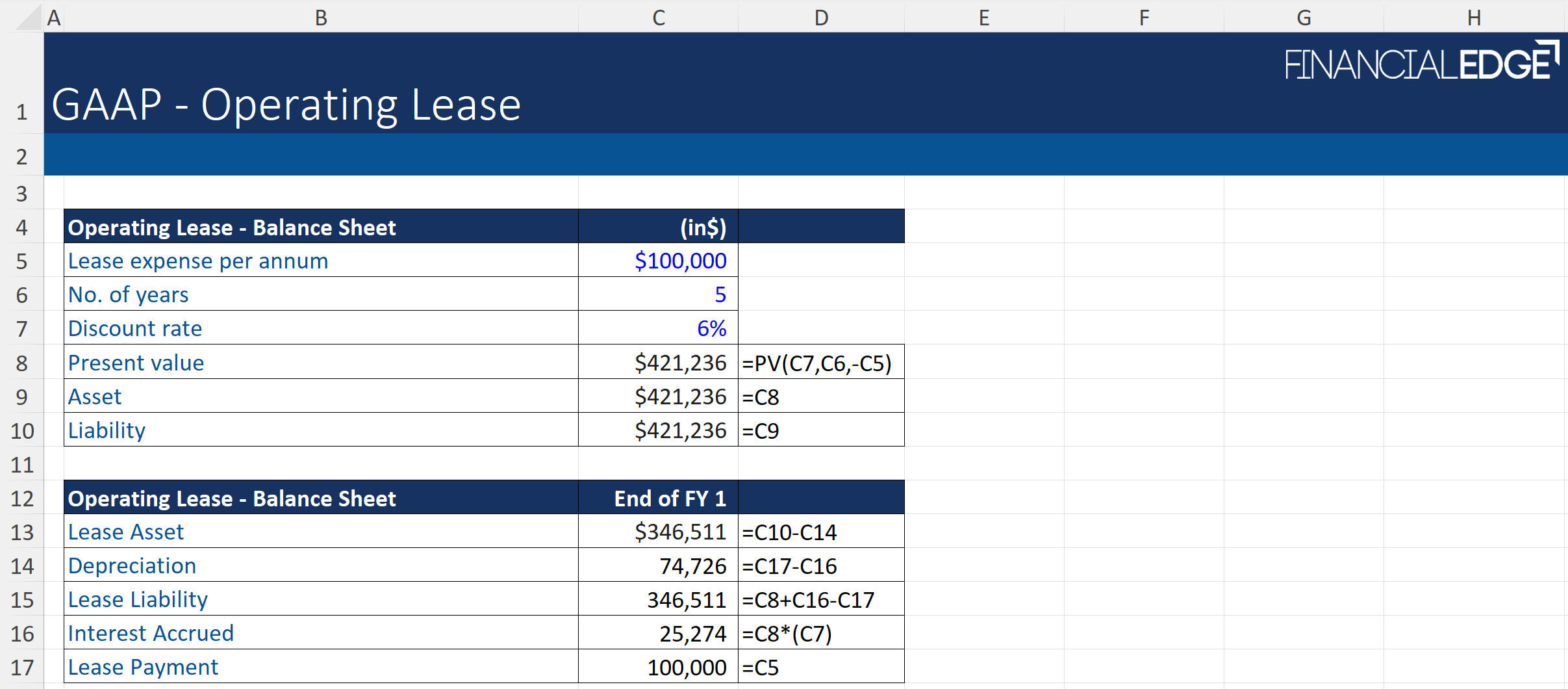

GAAP: Still maintains the classification between operating and finance leases. The treatment of operating leases is as follows:

- Balance Sheet: A lease asset and a matching lease liability are recorded at the outset, both measured at the present value of future lease payments. Over time, accrued interest is added to the opening lease liability and the lease payment is deducted to arrive at the closing liability. Lease asset is reduced by same amount, which is lease payment less accrued interest.

- Income Statement: A single lease expense is recorded each year, spread evenly across the lease term.

For example: For a 5-year operating lease of office space, with annual expense as $100,000 and discount rate of 6%.

Leases With More Than 12 Months of Term – Financial Lease

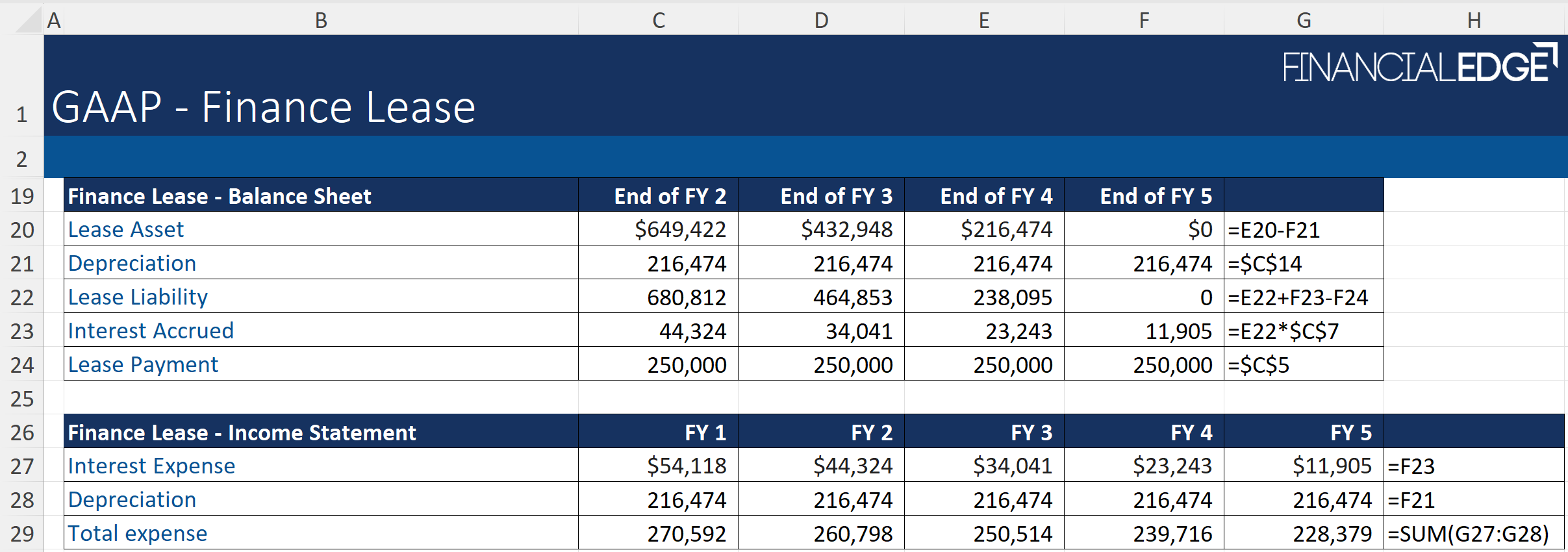

For finance leases, the accounting treatment is the same under both GAAP and IFRS:

Balance Sheet: A lease asset and a matching lease liability are recorded at the outset, both measured at the present value of future lease payments. Over time, accrued interest is added to the opening lease liability, and the lease payment is deducted to arrive at the closing liability. The lease asset is reduced by depreciation, which is calculated as the present value of the asset divided by its useful life.

Income Statement: Lease expense is recognized as two components – interest expense and depreciation. This creates a “front-loaded” pattern, meaning higher expense in the earlier years that gradually tapers off.

For example, for a 5-year finance lease of a critical mining machine with a 5-year life, an annual expense of $250,000, and a discount rate of 5%.

Revenue Recognition

While both frameworks – GAAP (ASC 606) and IFRS (IFRS 15) are highly converged, subtle differences can still create timing mismatches in revenue recognition for long-term contracts.

For example, involving a Software as a Service (SaaS) subscription with an early renewal option:

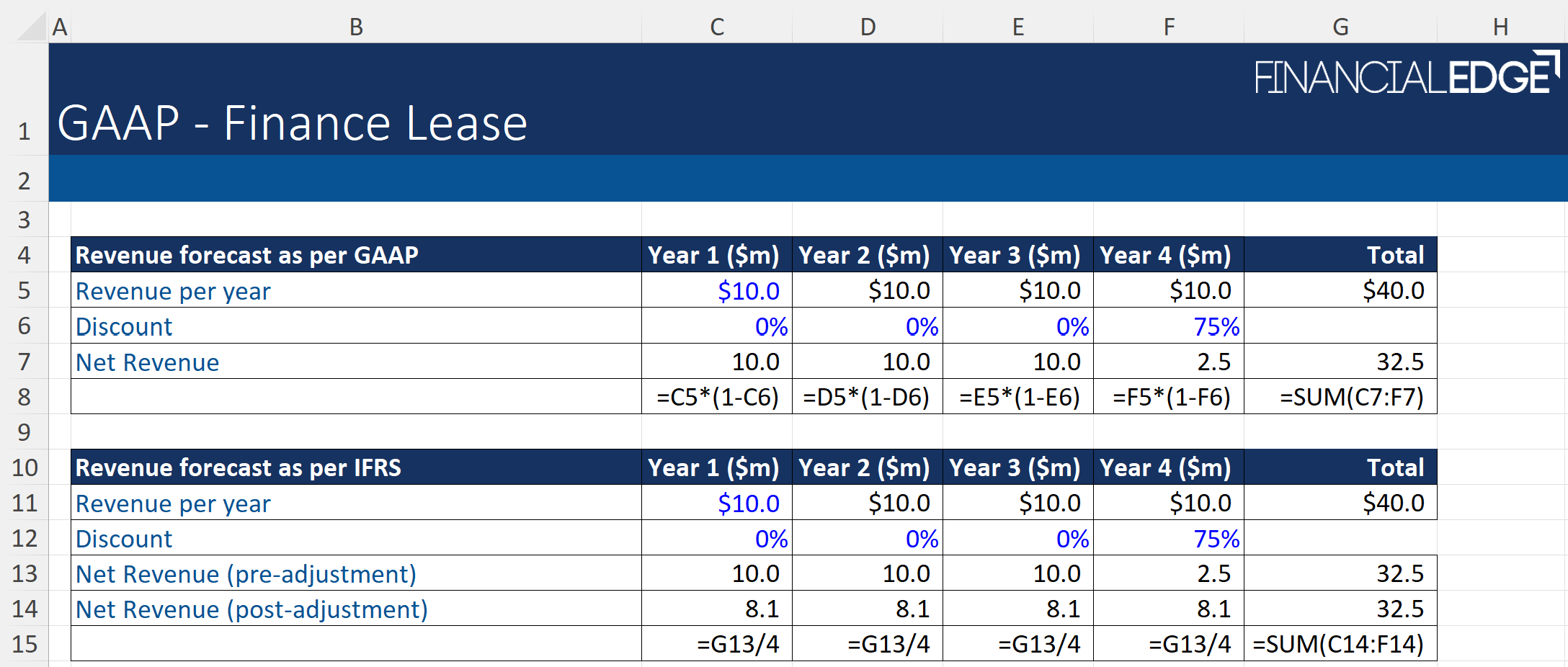

Scenario: Both a U.S. company (GAAP) and a European company (IFRS) sign identical 3-year contracts beginning January 1, 2026, of $10mm per year. The contract includes a renewal option for a fourth year at a deep discount of 75%, which the customer is very likely to exercise.

GAAP (ASC 606): Revenue of $10mm per year is recognized strictly over the 3-year term (2026–2028). The discounted renewal contract of $2.5mm is treated as a separate future performance obligation, so the fourth year is only recognized when it begins in 2029.

IFRS (IFRS 15): The renewal option may be treated as a “material right.” In that case, part of the initial transaction price must be allocated to the renewal from the outset. Revenue of $8.1mm is then recognized over the 4-year horizon (2026–2029).

Result: In the first three years, the IFRS reporter will recognize less annual revenue than the GAAP reporter, because revenue is spread across four years instead of three. This highlights how even converged standards can produce different timing patterns in financial results.

Impairments

Under IFRS, an impairment test is a single-step process that compares the carrying value of an asset to its recoverable amount (the higher of its fair value less costs to sell and its value in use). However, GAAP uses a two-step process: first, an asset is tested for impairment if its carrying amount exceeds the sum of its undiscounted cash flows; second, if it fails the first step, the asset is written down to its fair value. This difference can influence the timing and magnitude of write-downs

For example, A company owns a specialized manufacturing machine with the following financial details:

- Carrying Amount: $1,100,000 (the value currently on the company’s balance sheet)

- Fair Value Less Costs to Sell (FVLCS): $900,000 (what it could be sold for today)

- Value in Use (VIU): $950,000 (the present value of all future cash it’s expected to generate)

- Sum of Undiscounted Cash Flows: $1,200,000 (the simple, total sum of cash it will generate, without considering the time value of money)

IFRS Impairment Test (Single-Step)

Determine the Recoverable Amount: IFRS requires using the higher of the machine’s Fair Value ($900,000) and its Value in Use ($950,000). Hence, recoverable Amount is $950,000. Since, the recoverable amount of $950,000 is less than the Carrying Amount of $1,100,000, an impairment loss must be recognized.

Calculate Impairment Loss

Impairment Loss = Carrying Amount – Removable Amount

Impairment Loss is $1,100,000 – $950,000. The company must write down the asset’s value by $150,000.

GAAP Impairment Test (Two-Step)

Step 1: The Recoverability Test

- First, compare the Carrying Amount ($1,100,000) to the Undiscounted Cash Flows ($1,200,000)

- Since the Carrying Amount ($1,100,000) is less than the Undiscounted Cash Flows ($1,200,000), the asset passes the recoverability test

- The test stops here

Step 2: Measuring the Impairment Loss

- This step is not performed because the asset passed Step 1

The company recognizes $0 Impairment Loss.

Capital Market Implications

Cross-Listed Companies: For companies listed in multiple markets (e.g., a European firm trading on both the LSE and NYSE), a reconciliation between IFRS and GAAP figures is necessary. Analysts must be prepared to make these adjustments when comparing a cross-listed company to its domestic peers

M&A Transactions: Differences in accounting standards can materially affect purchase price adjustments and earnout clauses in a merger or acquisition. For example, if a company’s EBITDA under IFRS appears stronger than a GAAP-based peer simply because of different lease accounting, it can affect the valuation in a deal

Credit Analysis: The GAAP vs. IFRS treatment of liabilities can directly alter a company’s leverage ratios. Since these ratios are a key component of credit analysis, they can influence debt covenants, credit ratings, and a company’s borrowing capacity

What are Non-GAAP Measures?

GAAP provides precision, while IFRS provides flexibility. However, both can produce numbers that look similar on the surface yet diverge in ways that materially affect comparability and decision-making. For anyone building financial models, benchmarking peers, or advising on deals, understanding which standard applies, and making the necessary adjustments is non-negotiable.

Non-GAAP measures are financial metrics that adjust or supplement results reported under GAAP to present what management believes is a clearer picture of a company’s underlying performance. They typically exclude certain expenses or gains that are non-recurring, non-cash, or outside core operations.

Common Examples

Adjusted EBITDA

Adjusted EBITDA excludes interest, taxes, depreciation, amortization, and often further one-time adjustments like restructuring charges or stock-based compensation.

Core Earnings / Adjusted Net Income

Core Earnings / Adjusted Net Income excludes one-time items such as litigation expenses, asset sales, or impairment charges.

Free Cash Flow (FCF)

Companies have flexibility in how they calculate it. Some firms use “unlevered free cash flow” (before debt service), others “levered free cash flow” (after debt service), or adjust further for acquisitions, stock-based compensation, or one-time items.

Free Cash Flow = Operating Cash Flow (GAAP) – Capital Expenditures.

Why Non-GAAP Measures Matter

For analysts and bankers, non-GAAP measures are often more relevant for valuation. EV/EBITDA multiples, for instance, are almost always applied to adjusted EBITDA rather than GAAP net income.

They help normalize comparisons across peers, especially in industries with high non-cash charges (e.g., technology, pharma) or frequent restructuring.

They reveal management’s narrative of “true performance”, but also introduce risk if adjustments become overly aggressive or misleading.

Conclusion

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) are not just accounting rules, they are the foundation of trust in U.S. capital markets. By enforcing standardization, GAAP reduces information asymmetry, ensures comparability, and underpins valuations, credit assessments, and deal-making. For financial analysts, understanding GAAP, and knowing how to adjust for its differences with IFRS or management’s non-GAAP measures, is essential. It is this blend of precision and judgment that allows analysts to cut through the noise, extract the true economic picture, and make sound investment decisions.