UBS Announces Takeover of Credit Suisse

March 20, 2023

On Sunday 19th March, UBS announced their agreement to buy Credit Suisse for $3.25bn, creating one of the biggest banks in Europe with over $5 trillion in total invested assets. This followed negotiations brokered by Swiss regulators to safeguard the country’s banking system and attempt to prevent a global banking crisis. Credit Suisse shares collapsed by 60% the following Monday morning, while UBS traded 10% lower. Our Founder and Managing Director, Alastair Matchett, shared his reservations on the deal on LinkedIn, highlighting the short-term earnings dilution for UBS and the ‘meager’ takeover price. In this article, we explore this blockbuster deal in more detail.

To set the scene, Credit Suisse has faced a string of difficulties over the last two years. This included losing $5.5 billion when U.S. family office Archegos defaulted in March 2021, followed shortly by freezing $10 billion of supply chain finance funds after the collapse of Greensill Capital. Antonio Horta-Osorio also resigned as Chairman in January 2022, after flouting COVID-19 quarantine rules less than a year in the role.

More recently, Credit Suisse revealed “material weaknesses” in its control procedures and reporting for the past two years, which caused a sell-off in the lender’s shares. The announcement came after a delay in publishing the bank’s annual report due to an SEC regulatory probe. The bank’s troubles were compounded when top investor, the Saudi National Bank, said it would not provide further financial assistance. To restore investor confidence and shore up liquidity, Credit Suisse initially secured a $54 billion loan from the Swiss National Bank. However, despite these efforts, the bank’s share price dropped by 10% on Friday 17th March on fragile investor sentiment. Adding to the bank’s woes, it was reported that at least four major banks, including Société Générale and Deutsche Bank, had imposed restrictions on new trades with Credit Suisse. Analysts immediately began to speculate that the Swiss bank would be acquired by a rival bank.

At first, there were multiple reports of interest for Credit Suisse from rivals. Bloomberg reported that Deutsche Bank was considering buying some of its assets, while U.S. financial giant BlackRock denied a report that it was participating in a rival bid for the bank. In the end, UBS emerged as the frontrunner for the Credit Suisse takeover.

The ensuing weekend was marred in frantic negotiations between Credit Suisse and UBS, as the Swiss government used emergency measures to fast-track the deal without a shareholder vote. Time was of the essence to broker a deal, in order to avoid a potential bankruptcy of Credit Suisse altogether and prevent a deepening banking crisis.

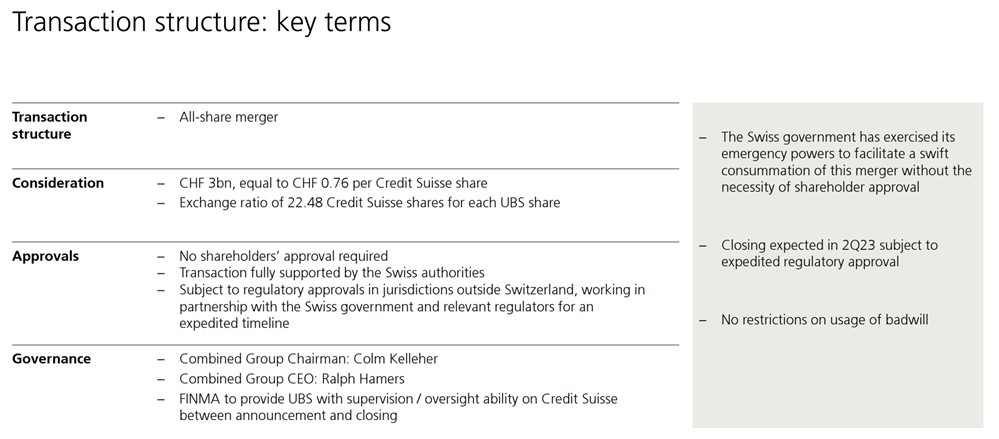

An official presentation published by UBS on Sunday 19th of March highlighted the key terms of the deal, including the transaction structure, consideration and approvals process entailed. As part of the all-share merger, Credit Suisse shareholders will receive 1 UBS share for every 22.48 Credit Suisse shares held, equivalent to 0.76 per share, far below Credit Suisse’s previous closing price of 1.86 Swiss Francs (CHF). The Swiss National Bank has also agreed to offer a liquidity line of CHF 100bn backed by a federal default guarantee to UBS in an effort to shore up confidence, while loss protection of CHF 25bn was agreed to support purchase price adjustments and restructuring costs.

Source: UBS presentation on their acquisition of Credit Suisse

At first, investors were clearly not convinced about the long-term benefits of the rescue deal, with the Credit Suisse share price tumbling 60% on the morning following the announcement, while the UBS share price dropped 10%. Investors were unnerved in particular by the losses imposed on owners of $17 billion worth of Credit Suisse bonds. These bonds made up part of the bank’s Additional Tier 1 (AT1) debt, a form of junior debt that counts towards banks’ regulatory capital. Investors were surprised that shareholders, who sit below AT1 bondholders in the debt repayment hierarchy, are set to receive CHF 3 billion, while AT1 bondholders assume losses. It has recently emerged that The Bank of England has since moved to clarify the order in which shareholders and creditors should bear losses in a bank resolution or insolvency case. In a turn of events, the UBS share price recovered during intra-day trading to a 5% gain, as investors weighed the steeply discounted takeover price and the downside protection given to UBS.

As Alastair alludes to in his post, the takeover price is so low that it might turn into a ‘terrific deal’. This is heavily reliant on the turnaround process of Credit Suisse, and how UBS can realize the CHF 8bn of cost synergies mentioned in the presentation. Further details are yet to emerge on any restructuring plans, and questions remain as to how much this will cost and to what extent UBS can absorb these restructuring costs. It is also worth highlighting the big difference in risk culture between the banks, as UBS Chairman Colm Kelleher commented: “We will be de-risking a lot of the tricky businesses that we are inheriting”. Part of UBS’ derisking plan is to downsize Credit Suisse’s investment banking business, with the merged investment banks not to account for more than 25% of the total firm’s risk-weighted assets in the future.

While the merger has been agreed upon, it is not over the finish line yet – the deal is expected to close by the end of this year.