How to Monitor Portfolio Performance starts with understanding that portfolio performance monitoring is the ongoing process of measuring and analyzing how an investment portfolio performs over time relative to its objectives and constraints. Instead of simply looking at end-of-period results, it evaluates the return generated by the portfolio, the level of risk taken to achieve those returns, and how the outcomes compare with an appropriate benchmark or investment goal. The process relies on consistent calculation methods, suitable performance and risk metrics, and a clear understanding of the impact of cash flows, time horizon, and prevailing market conditions.

How to Monitor Portfolio Performance

February 20, 2026

What is Portfolio Performance Monitoring?

Key Learning Points

- Performance monitoring is the process of evaluating the portfolio’s returns, risk, and consistency relative to a benchmark and/or objectives

- Time-weighted and money-weighted returns measure different outcomes and should be used appropriately – the timing and size of cash flows may have a significant impact on results

- Market-based comparisons evaluate relative performance, while goals-based reviews examine the progress toward a specific outcome

Short-Term and Long-Term Investments

In order to choose an appropriate monitoring approach, investors would need to consider the investment horizon of the portfolio. Generally, there are two categories:

Short-term Investments

Short-term investments are typically evaluated over shorter periods, daily, weekly, or monthly. The main focus is on risk metrics such as volatility and drawdowns, along with liquidity, and even small deviations from the expectations can trigger the reallocation of capital. Examples of such strategies include tactical allocation portfolios and trading strategies.

Long-term Investments

Long-term investments have long-term objectives and therefore evaluation focuses on compounding, and the ability to deliver consistent performance through market cycles (i.e. multi-year periods). Interim volatility is normally considered in the context of long-term objectives rather than short-term noise, which prevents unnecessary turnover and inefficient decision-making. Examples of such investments are retirement portfolios, endowments and long-only equity strategies.

Portfolio Performance Metrics You Must Track

Performance monitoring involves tracking a range of metrics, which broadly fall into three categories, return measures, risk measures, and risk-adjusted performance measures. Each of these categories reveals a different aspect of how the portfolio behaves.

Return metrics focus on how much value the portfolio has generated over a specific time period. Measures such as absolute and relative returns (typically annualized) are used to quantify overall growth and consistency. These measures are often among the first figures investors look at, but on their own they provide limited insight.

Risk metrics, on the other hand, examine the level of uncertainty in portfolio outcomes. Volatility is the most commonly used risk measure and reflects how widely returns fluctuate over time. More volatile portfolios experience larger shifts in value. Another example of a popular risk measure is the maximum drawdown, which is the largest peak-to-trough fall in the value of an investment before a new peak is achieved.

Risk-adjusted return metrics combine return and risk into a single framework. The Sharpe ratio is a widely popular example, which evaluates how much excess return a portfolio generates for the level of risk taken. These measures help investors assess whether higher returns are the result of skill or simply greater risk exposure.

Time-weighted vs. Money-weighted Returns

The time-weighted and the money-weighted returns are the two major approaches to measuring investment performance.

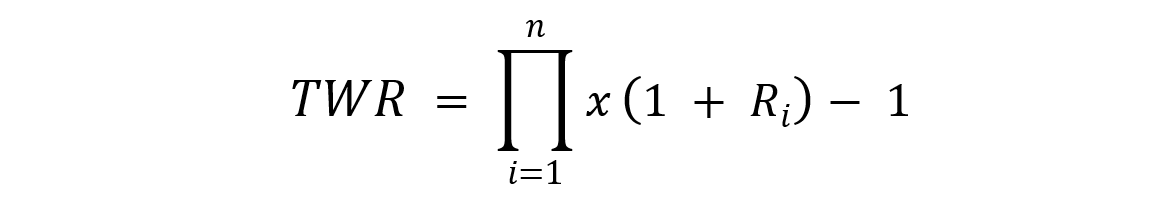

Time-Weighted Return (TWR)

This type of return measures the performance of an investment portfolio independent of cash flows. It essentially breaks the total measurement period into sub-periods defined by external cash in- or outflows, and then geometrically links the returns for each sub-period.

Where:

- TWR – The time-weighted return over the full evaluation period. It represents the cumulative performance of the portfolio after linking all sub-period returns.

- i – Index for each sub-period. A new sub-period begins whenever an external cash flow (contribution or withdrawal) occurs.

- n – The total number of sub-periods in the measurement period.

- Ri – The portfolio return earned during sub-period , calculated as the change in portfolio value during that sub-period (excluding external cash flows).

The product operator indicates that returns are geometrically linked and reflects the compounding nature of investment returns over time.

This approach removes the effect of portfolio decisions (security selection and asset allocation) through neutralizing the timing and size of contributions and withdrawals. It is an industry standard for evaluating investment funds and a preferred reporting method under the CFA Institute’s Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS). It is also commonly used among asset managers, investment consultants and institutional investors to compare strategies as it ensures that managers are not rewarded or penalized for cash flow decisions that are outside their control.

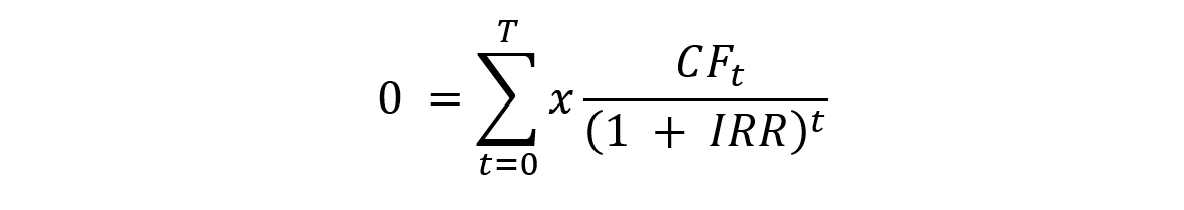

Money-Weighted Return (MWR)

Money-weighted return takes into account both investment performance and the timing of cash flows. It measures the return actually earned by the investor and is typically calculated as the internal rate of return (IRR).

Where:

- IRR – The internal rate of return, which represents the money-weighted return earned by the investor over the entire investment horizon

- t – The time index indicating when each cash flow occurs.

- T – The final time period in the analysis.

- CFt – The net cash flow at time . outflows are recorded as negative values, whereas inflows are recorded as positive values

- (1 + IRR)t – The discount factor used to convert each cash flow to its present value at time

The equation solves for the discount rate that sets the present value of all cash flows equal to zero.

This method is highly sensitive to periods when contributions and withdrawals occur. For example, adding more funds prior to a period of strong performance increases the money-weighted return. Money-weighted returns are most appropriate for private market investments as the timing of cash flows is a key part of the investment outcome. Private equity, real estate, and infrastructure funds typically report IRRs.

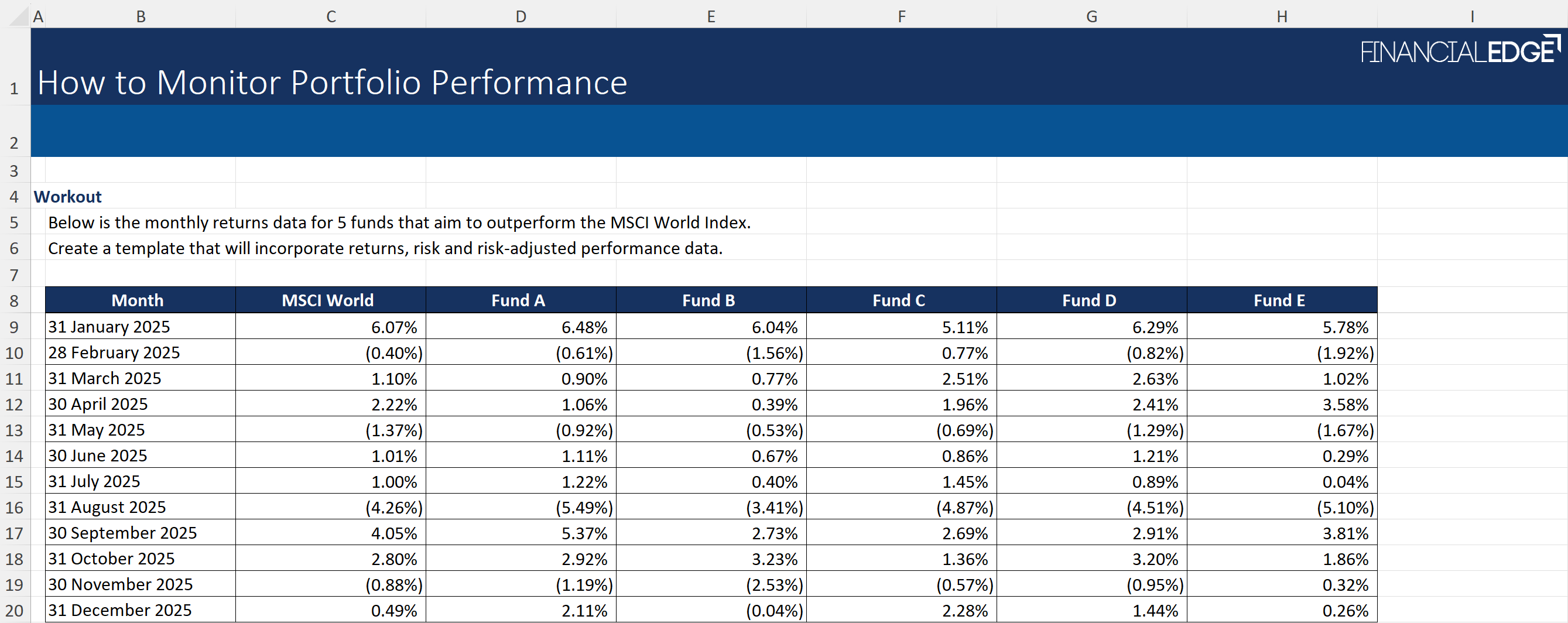

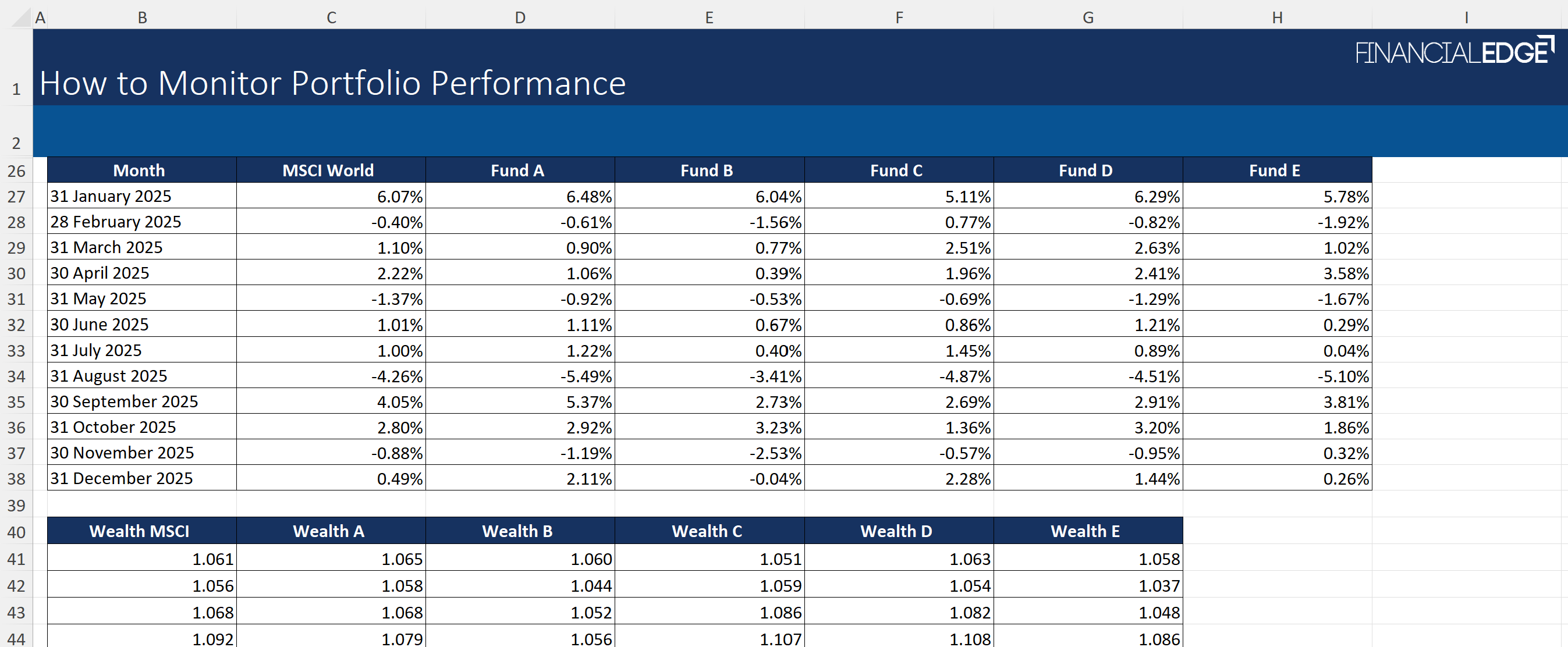

How to Monitor Portfolio Performance Example

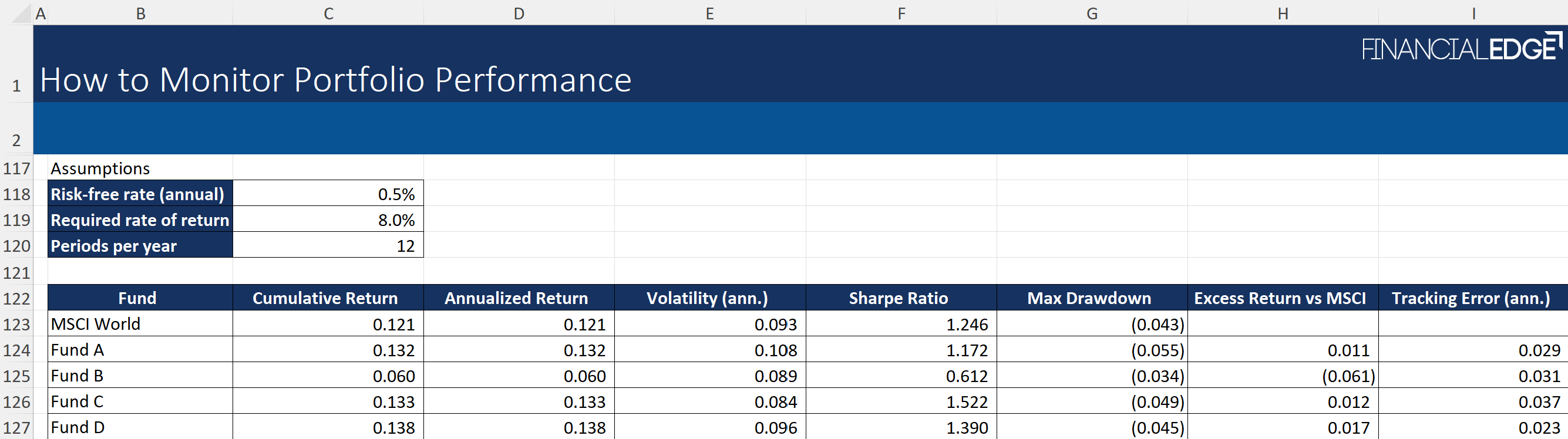

Below is a practical example of how portfolio performance monitoring is conducted. It calculates key metrics for equity funds against a benchmark.

(click to zoom)

The model uses historical returns to guide investors through measuring performance, risk and risk-adjusted returns return, and relative performance through ratios such as volatility, Sharpe ratio and tracking error. The aim is to create a framework for interpreting investment outcomes and comparing funds consistently.

(click to zoom)

(click to zoom)

How to Define Your Required Rate of Return?

The required rate of return (RRR) is the minimum return that an investor needs to meet the desired objectives, risk tolerance, and time horizon. It serves as a performance hurdle – if a portfolio performs well against its benchmark, but consistently struggles to achieve its RRR, it may fail to meet long-term goals.

A commonly used framework for estimating the RRR is the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), where the required return is equal to the risk-free rate plus a risk premium that compensates the investor for exposure to market risk.

Measuring Portfolio Returns Over Time

Measuring portfolio returns over time resolves the challenge that a single period present – results may be heavily influenced by the selected start and end dates. The market conditions around those dates can distort conclusions and make performance appear better or worse than it actually is.

Using rolling returns instead resolves this issue as they assess performance over overlapping periods of equal length.

This method generates a series of returns calculated at regular intervals (for example rolling 3 or 5-year returns). Each data point indicates how the portfolio would have performed if an investor had entered the portfolio at a different point in time and held it for the same duration.

The Difference Between Goals-based and Market-based Portfolio Reviews

The two most popular approaches to performance evaluation are market-based and goals-based reviews. Relative returns are the core focus of market-based performance. Investors typically evaluate the portfolio’s performance against a market index or a peer group average comprised of similar strategies. For example, a global equity fund might be evaluated against the MSCI World Index, as well as a selected group of funds that exhibit similar features in terms of style or size (as per the portfolio’s average market cap). Outperformance over a specific period may be an indication that the manager added value. This method is widely used by institutional investors, mutual fund rating agencies, and consultants as it provides a standardized approach to compare managers.

On the other hand, goals-based reviews focus on the progress toward specific investor objectives. For example, a retirement plan may set a target to accumulate $1 million over a 20-year period. In this case, investors will examine whether the portfolio’s current trajectory (taking into account contributions, withdrawals and forecasted returns) is likely to achieve that target.

Goals-based reviews are popular in areas such as wealth management, retirement planning and liability-driven investment strategies. It reduces the obligation to chase relative outperformance, which can sometimes add more undesired risk.

Common Mistakes in Portfolio Performance Monitoring

Although the portfolio performance monitoring process should be built around the specific features of the strategy, there are a few common mistakes:

- Putting too much attention on short-term performance. This usually increases sensitivity to market noise and may result in reactive decisions and unnecessary portfolio turnover.

- Focusing on raw returns while ignoring risk-adjusted measures also makes it difficult to assess whether performance is adequate relative to the risks taken.

- Using inappropriate benchmarks can distort performance conclusions.

- Confusing money-weighted returns with manager skill. Cash flows can significantly affect performance, even when the underlying investment strategy performs consistently.

- Not accounting for data frequency in the calculations (for example, weekly or monthly returns without appropriate annualization) can distort volatility and risk-adjusted metrics.

Conclusion

To sum up, portfolio performance monitoring is a key part of the ongoing investment management process and expands beyond just looking at returns. Most important is taking into account how the returns were generated, the level of risk taken, and whether outcomes align with relevant benchmarks and objectives. Using appropriate measures and accounting for the impact of cash flows allows investors to get a better perspective of the portfolio’s behaviour and distinguish manager skill from market-driven effects.

Additional Resources

Portfolio Management Certification

Portfolio Management Interview Questions

Portfolio Optimization

Portfolio Performance