Tail Risk

August 19, 2025

What is Tail Risk?

Tail risk is the term used in financial markets to describe the probability of rare and extreme market events. Such events would almost always occur in the “tails” (i.e. far away from the arithmetic mean) of a probability distribution curve. Although statistically infrequent, they would often result in disproportionately large losses. During such events, asset prices tend to deviate significantly from their historical averages. Recent examples include the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the 2020 Global Pandemic selloff, which impacted financial markets worldwide.

Tail events are typically a result of sudden liquidity shocks, systemic shocks or geopolitical instability. Investors are increasingly focusing on tail-aware risk measures such as Conditional VaR which awards greater risk weightings to these unlikely but very damaging scenarios.

Traditional risk models like variance or Value at Risk (VaR) tend to underestimate tail risk as they assume normal distributions and downplay extreme outcomes. Tail risk is highly applicable for leveraged portfolios, structured products and/or institutions with capital preservation mandates.

Key Learning Points

- Tail risk is described as the extreme market outcomes lying far in the return distribution’s tails which are rare but can cause disproportionate portfolio impact

- It is typically measured by using spectral risk measures such as the Conditional VaR (CVaR), as traditional models tend to underestimate the severity of such events

- Notable examples of tail risk events include the 2008 Global Financial Crisis or more recently the Global Pandemic Selloff in 2020

- Common strategies that help mitigate tail risk include diversification, hedging or dynamic allocation and stress testing

Tail Risk Explained

Analyzing the likelihood and the potential impact of extreme negative outcomes is key to understanding tail risks. Tail Risk is defined as more than three standard deviations from the mean. Traditional risk metrics such as volatility or Value at Risk (VaR) would usually underestimate the severity and the frequency of tail events. As they typically lie at the far ends of the return distribution curve tail risks suggest skewed distribution of returns and fatter tails, as opposed to normal distribution.

To more accurately account for such risks, investors use sophisticated metrics, such as Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR). This estimates the average loss in the worst-case scenarios beyond a specified percentile (le, the worst 5%). Other approaches include stress testing and scenario analysis or analyzing where portfolios have been subject to historical crises to establish the level of potential drawdowns.

Quantifying tail risk is particularly important for various financial institutions where large and unexpected losses can threaten their solvency. These include banks, insurers, pension funds and hedge funds. In addition, regulators have also adopted using tail risk focused metrics under frameworks such as Basel III and Solvency II to ensure institutions hold sufficient capital buffers against extreme losses.

Normal Distribution and Asset Returns

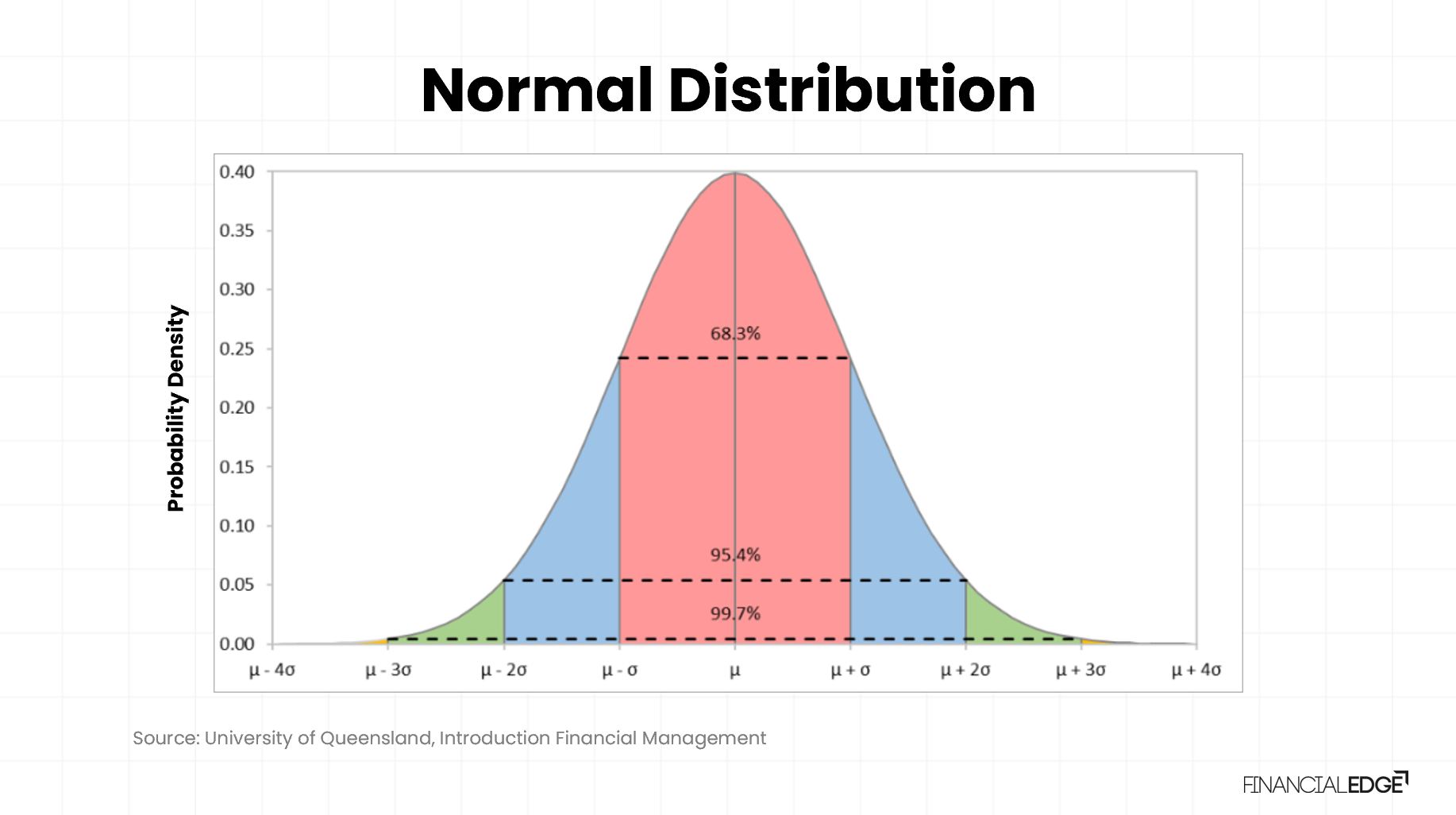

The traditional approach of modelling asset returns is by using a normal distribution – a bell-shaped curve that is characterized by its mean (average return) and standard deviation (volatility). Under this assumption, most of the returns cluster near the mean, where extreme outcomes (positive or negative) are rare. To put this into perspective, approximately 68% of the returns fall within one standard deviation and 95% of the returns within two standard deviations (as shown on the chart below).

Although this framework simplifies risk modeling, the real-world returns often exhibit fat tails and skewness, meaning that extreme events occur more often than predicted.

Is Left Tail Risk Better than Right Tail Risk?

Left tail risk refers to extreme negative returns (i.e. large losses) while right tail risk refers to extreme positive returns or large, unexpected gains. While the latter is generally more desirable, left tail events can lead to permanent capital loss. In such cases, downside shocks could have much greater consequences in eroding capital and investor confidence far more severely than missed upside opportunities.

Therefore, in financial risk management left tail risk requires more active monitoring and mitigation by using some of the approaches we discussed above – diversification, hedging or stress testing.

Example of CVaR and How it is Used

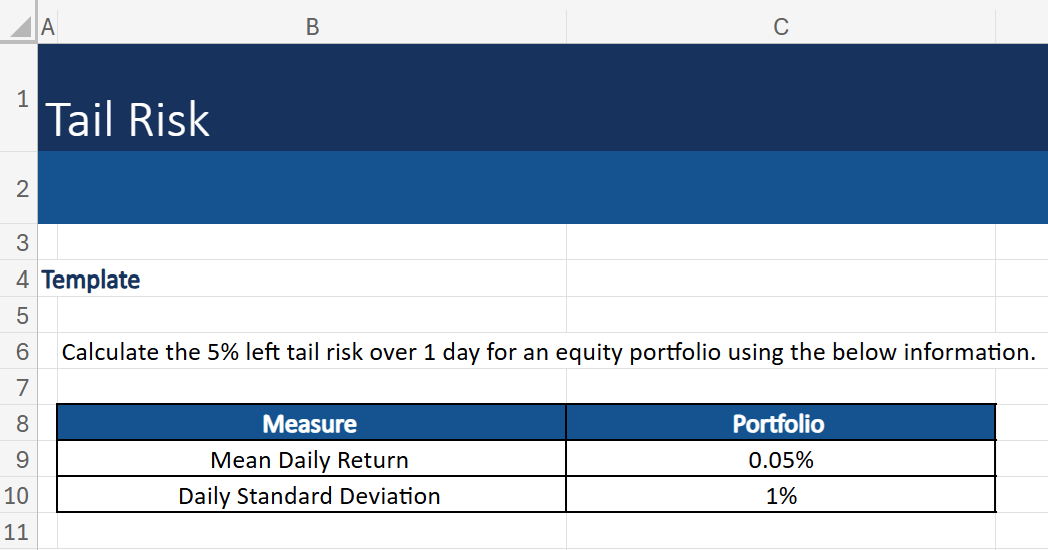

In the workout for this blog, we provide a practical example of how CVaR is used and interpreted.

Steps to Calculate CVaR

Download the free Financial Edge template to discover all the formulae and calculations required for conditional variance at risk.

1) Steps to Calculating VaR

Looking at the data provided, we firstly need to calculate the Value at Risk at 95% confidence for the left-tail loss threshold.

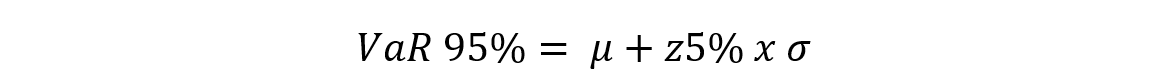

This can be done using the formula below:

VaR 95%= μ+z5% x σ

Where:

µ = the mean daily return of the portfolio

z5% = the z-score corresponding to the 5% left-tail probability in the standard deviation

σ = the standard deviation of the daily returns

2) Calculate the Z-Score

To calculate this equation, we need to calculate the z-score, which we can do in excel using the following formula: =NORM.S.INV(0.05) which gives the answer -1.645

3) Calculate the Value at Risk score

Then we apply the VaR formula above which equates to: = 0.05% + (-1.645 x 1%) = -0.01595

This means that on the worst 5% of days, losses exceed 1.595%.

4) Calculating Conditional Value at Risk

The next step is to calculate Conditional Value at Risk which is the average loss beyond VaR.

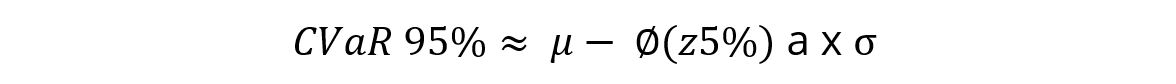

This is the formula we need to use:

CVaR 95%≈ μ- ∅(z5%) a x σ

Where:

∅(z5%) = the probability density function (PDF) value of the standard normal distribution at z5%

a = the tail probability

σ = the standard deviation of daily returns

The CVaR for this is calculated at -2.062 meaning that in the worst 5% of cases, the average loss is 2.06% per day.

Why is Tail Risk Important?

Tail risks are very important because their impact can be catastrophic. Standard risk metrics would usually dismiss the potential severity of such events, which leaves portfolios exposed to high levels of financial stress. Recent studies that analyze traditional 60/40 portfolios (i.e. 60% invested in equities and 40% in bonds) established that historical maximum drawdowns of approximately 49.2% were reduced down to around 27% by using tail-risk mitigation strategies (reduction in peak losses of over 22%) (Absolute Momentum, Sustainable Withdrawal Rates and Glidepath Investing in US Retirement Portfolios From 1925). These figures further stress the importance of tail risk modelling and why a variety of financial institutions from hedge funds to insurers prioritize it.

The implementation of effective tail risk measures support capital preservation and could avoid forced asset liquidation (also known as “forced selling”) during periods of extreme market volatility and maintain solvency. On the other hand, investors that ignore tail risks may end up in a situation where their portfolio is mispriced, which in turn could have a severe impact on their long-term objectives.

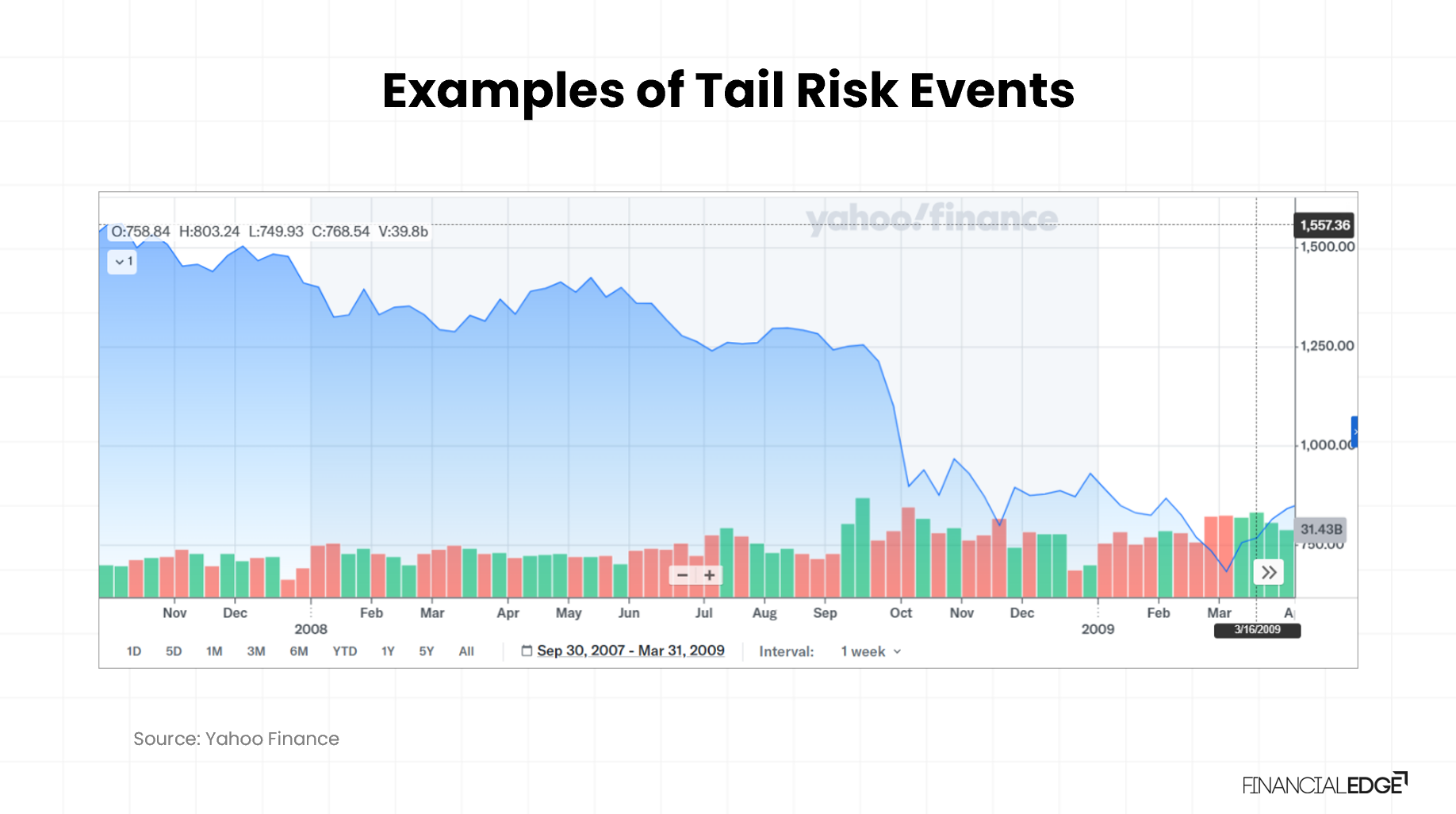

Examples of Tail Risk Events

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) from 2008 is one of the most notable tail risk events in modern financial history that revealed ignoring tail risk can lead to catastrophic losses, liquidity shortages and long-term reputational damage. The GFC started with the collapse of the US housing market and the widespread failure of mortgage-backed securities (MBS), resulting in extreme market dislocations and systemic liquidity shock. To show the magnitude of the crisis, the S&P 500 Index fell by more than 55% from its peak (for the period between October 2007 and March 2009, as shown on the chart below), wiping out trillions off its market capitalization.

This level of drawdown was a multi-standard-deviation event that far exceeded normal volatility expectations. This explains why the traditional Value at Risk (VaR) models significantly underestimated it and many portfolios experienced correlated losses across asset classes as credit spreads widened sharply and the demand for safe-haven assets like US Treasuries increased drastically. As a result, some institutions such as the leading investment bank Lehman Brothers failed outright, while others required massive government intervention to survive. An example is one of the world’s largest insurers – American International Group (AIG), which received a $182bn rescue package, making it one of the largest bailouts ever.

Common Strategies for Managing Tail Risk

There are various strategies that can help mitigate tail risk. Below we look into three of the most common across different investor types.

Diversification

While it may appear as relatively simple, diversifying a portfolio across uncorrelated (meaning either having negative or low correlation) assets is essential to managing tail risk as it reduces reliance on any single asset class and limits exposure to large drawdowns. Spreading the funds of a portfolio across different asset classes such as equities, fixed income, real estate or alternatives can significantly reduce its sensitivity to market shocks.

This approach is popular with institutions that are required to prioritize long-term capital preservation and the predictability of returns, for example pension funds. A diversified portfolio would ensure that even if equities suffer large drawdowns, other asset classes such as Treasuries or gold may offset losses.

Hedging by Using Derivatives

Institutions that run leveraged strategies are highly sensitive to drawdowns and would typically use options, swaps or other derivatives to explicitly protect against extreme downside events. Hedge funds are a typical example. They may buy put options on the S&P 500 index, which can provide large payoffs during sharp market declines, and offset losses. Although this could be a costly solution, it acts as “insurance” against severe drawdowns and allows maintaining higher exposures while mitigating catastrophic loss scenarios at the same time. This level of flexibility is highly important for hedge funds as it helps them remain invested in higher return areas of the market.

Dynamic Risk Allocation and Stress Testing

Institutions that operate under strict regulatory risk frameworks such as banks and insurers, require regular stress testing and capital adequacy planning. Stress testing uses extreme, but plausible scenarios to identify vulnerabilities before they materialize, while the dynamic risk allocation involves ongoing adjustments to the portfolio based on real-time risk assessments. These include volatility signals and stress-test outcomes. For example, reducing the portfolio’s equity allocation when implied volatility spikes, or reallocating into cash and safe-haven assets when macroeconomic indicators deteriorate. Such a de-risking move could prevent insolvency and preserve liquidity.

Conclusion

Tail risk refers to the rare market events that can potentially be highly damaging to an investment portfolio. Analyzing and understanding tail risks is key in implementing robust risk mitigation strategies.

Financial institutions that aim to preserve capital such as banks, insurers and pension funds, as well as others that run higher risk portfolios like hedge funds, would place critical importance on mitigating tail risks through various strategies.